Private Libraries in Ancient Rome

Figure 1 – the Villa of the Papyri, East Side

Private Libraries in Ancient Rome

(c) Jerry Fielden 2001

In 753 BC, date of the mythical founding of Rome, its citizens were not too

preoccupied with libraries and probably almost totally illiterate. Apart from

laws and annals, it is not until the second century BC that we hear about

literacy and libraries becoming a force in the fabric of Roman society. Even

then, these were surely limited to the senatorial and equestrian aristocracy and

the top ranks of the soldiers, even though graffiti and other writings seem to

contradict this somewhat. From Varro to Suetonius, from Vitruvius to Ammianus

Marcellinus, plenty of Roman writers talk about this subject during the period

that concerns us the most, mainly between 100 BC to 500 CE. Private libraries

figured prominently in this period, and it is probably because of them that we

still have many texts from the Roman world that would have not survived if left

only in the public libraries of the day, which had a tendency to be destroyed

during wars or natural disasters - and burned easily.

The first libraries in Rome were certainly private. In the mid-2nd century BC,

Rome was a nation of farmer-warriors that conquered the Hellenistic World by

force of arms. Curiously, the conquerors were themselves subjugated by the

culture of the losers – almost to the point of reverence,[1] and Roman mores

and culture were revolutionized from that point on. Roman generals coming back

from the East would return with booty, including the books that became the basis

for some of the biggest private libraries in Rome, and even the kernel of the

soon-to-be-founded public libraries. Some examples of these generals are

Aemilius Paulus, Cornelius Sulla and Lucius Lucullus. Aemilius won against

Macedonia’s King Perseus in 168 BC and allowed his soldiers to take plenty of

booty, but he himself kept only the King’s library, which he gave to his two

sons; this occurrence eventually started the friendship between Aemilius’s son

Scipio Aemilianus and the Greek historian Polybius, one of the turning points in

the Greek influence on Roman mores.[2] Sulla, who was to become the infamous

bloody dictator we all know, defeated Athens in 86 BC and took the library of

Apellicon of Teos, which contained part of the famous philosopher Aristotle’s

library. Lucullus defeated the King of Pontus around these times as well, and

seized the library of the King and put all the books in his own private library,

which he allowed friends and scholars to consult.[3] Mark Antony made a gift to

Cleopatra of 200,000 volumes from the library at Pergamum, that the Roman armies

had looted.[4] There were lots of private libraries at this point, but no public

ones as of yet, so the dictator Julius Caesar charged Terentius Varro, a learned

associate of his and a well-known collector, to found a public library in Rome

by gathering and classifying all the books he could find,[5] a plan that was

foiled by the assassination of the dictator-for-life. Eventually, G. Asinius

Pollio probably brought together several collections from other Romans of note,

such as Varro’s and Sulla’s, and founded the first public library in Rome,

at the Temple of Liberty in 39 BC.[6] He probably used the booty from the wars

against the Parthini to accomplish this.[7] It is around those days that the

Roman system of government changed from an oligarchy to an effective monarchy.

The Emperor (or princeps) took over the supervision of the public libraries of

Rome. Augustus, the first emperor, founded at least two public libraries in

Rome. His successor, Tiberius, founded one as well, and also had an extensive

private library in his palace. Vespasian founded one in 75 CE with the booty

from Jerusalem. Domitian possibly founded a library (or this may have been done

by Hadrian), and made sure the libraries that were damaged by fire during

Nero’s reign were restocked with books.[8] Trajan, in 114 CE, founded the most

famous Roman public library, the Ulpian Library, in the forum that bears his

name. This library was moved, entirely or in part, to the Baths of Diocletian in

the 4th century CE, and apparently returned to its original location later

on.[9] Indeed, in 480 CE, it is recorded that the library still existed.[10]

Hadrian built a library in Athens and one or possibly two private libraries in

his palace at Tivoli.[11] Alexander Severus founded a library in the Pantheon at

Rome in the 3rd century CE. In the 4th century CE, Christian libraries became

prominent, and some emperors, such as Diocletian, attempted to destroy them as

part of persecutions, but many of the collections survived. Julian, the last

pagan emperor, also established a library in Antioch in 361 based on the library

of George, the Bishop of Alexandria, but this library was burned by Julian’s

successor Jovian.[12] Libraries were also built in the provinces by wealthy

benefactors, such as Pliny the Younger (a writer of note and an official under

Trajan) who built and endowed a library at Comum in North Italy.[13] He had

probably seeded this library with his uncle Pliny the Elder’s notebooks, and

also established a fund for its upkeep. This gesture by Pliny seems to have

started the trend in library-building by wealthy Romans across the Empire.[14]

Other examples include the libraries built by the consul Celsus at Ephesus,[15]

the priest Pantainos at Athens, and the orator Dio Chrysostom at Prusa.[16] Also,

private libraries became plentiful in the provinces, in the 2nd century and

later.[17]

Roman libraries, either of the public or especially of the private variety, were

probably initially not open to the general public, but only to the aristocracy,

to writers and to scholars. It was possible that the public was let in for

public recitations of works, but not particularly for book-borrowing. On the

wall of one library from Athens, an inscription was found that stated: “No

book shall be taken out, since we have sworn an oath to that effect…”.[18]

Only a privileged few could actually take books out or attempt it, such as the

Emperor himself or high officials of the Empire. Augustus even used the

“public” Palatine library as a meeting hall, so I doubt that many members of

the urban Roman masses were allowed to flock to the library on such days to read

and borrow books, or even to be in the library at all.[19] The future emperor

Marcus Aurelius, in his youth, had borrowed some books by Cato the Elder from

this library at one point and suggested to Cornelius Fronto that he go to a

different public library, the domus Tiberiana, to get the same texts and that he

must try to bribe the librarian to get a copy of them.[20] This is not exactly

what I would call a “public” library. Indeed, I too believe that the domus

Tiberiana, being part of the palace, was more of a private library.[21] We can

see here that the line could be rather blurred between “public” and

“private” in Ancient Rome. Before the principate, there were only private

libraries and the owners could let their clientele use them as an additional

privilege. Eventually, the aristocracy came to see a possibility of a public

library in the same fashion as any other “amenity to be bestowed to the lower

classes”,[22] like the games or baths. But private libraries were just that -

private. Very few had ever opened their doors to the public, except maybe

Lucullus’s, and even at that, to “selected” members of the public.

Private libraries were also considered to have better and more reliable copies

of texts: public libraries’ resources were not recommended because they were

so full of errors.[23] Even so, to have a work in a public library meant that it

was a finished work, “released” by the author and not subject to revisions,

in the “public domain” so to speak.[24] This also meant the author was

famous and that his work was considered an “established classic”,

“canonized” in a fashion.[25]

A further drawback to public libraries in Rome was that they were affected by

censorship: we know that Augustus forbade the works of Ovid upon the poet’s

disgrace and also some works from Julius Caesar’s youth.[26] Later on, most of

the emperors until Constantine banned Christian works, and in turn the

victorious Christians later banned pagan works, and destruction was attempted on

both sides.[27] I doubt that private libraries were much affected by these

however: a case in point is that there was no massive destruction of Christian

private libraries under Diocletian’s persecutions.[28]

Famous owners of private libraries were Cicero, Atticus, Quintus, Varro, and of

course, the emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Hadrian, and others. Private libraries

were so popular that the architect Vitruvius included plans for them as a

matter-of-fact when designing Roman homes.[29] There came a point that there

were so many private libraries in Rome, that Seneca and Petronius both ridiculed

the owners of these because the books were used as decorations instead of for

their intended purpose.[30]So much of this misuse was happening that some think

that the famous line by Ammianus Marcellinus, “In short, the place of the

philosopher the singer is called in, and in place of the orator the teacher of

stagecraft, and while the libraries are shut up forever like tombs, water-organs

are manufactured and lyres as large as carriages…” refers to the total

disuse of private libraries by the late 4th century because of the predominance

of light entertainment over serious reading, and not of public libraries as many

authors like C.E.Boyd believe.[31] But, even at the end, on the western

frontiers of the Empire, private libraries still existed and flourished and many

became part of the monastic system that was to perpetuate writings during the

medieval period.[32]

Architecturally, libraries, public and private, were mostly divided in two rooms

or sections in Ancient Rome: a Latin section and a Greek one. Sometimes these

would be housed in different buildings. One author has compared this to the

Mouseion and the Serapeum in Alexandria.[33] A typical library would have the

collection in one or two rooms (Latin and Greek) with an enclosed (or separate)

reading room. On the walls would be niches to house the collection with a podium

or steps to allow access.[34]The libraries were shaped like a long hall, or

eventually, like a semi-circular room. There would be decorations such as

statues and portraits. Nearby reading rooms would sometimes be provided as well.[35]Armaria

(a type of shelving or storage box) were used copiously and a decorative central

niche might be seen in some libraries.[36] Eventually, some elements of storage

had to change, because the vellum codex was replacing the papyrus roll.[37]

Vitruvius says that the library “should face towards the East”, because of

the morning light, and so the books would not rot because of worms and dampness

caused by a wrong orientation.[38] The main architectural elements of Roman

private libraries were described quite well by Lorne Bruce: “wall niches,

apses, vaulted ceilings, curvilinear design, separate collections, narrow

corridors for humidity control, balconies, different axes of symmetry, central

decorative niches, united reader and storage space, and independence from the

portico…”.[39]

The books themselves consisted of “rolls of papyrus smoothed with pumice and

anointed with cedar oil, with projecting knobs of ivory and ebony, wrapped in

purple covers, with scarlet strings and labels”.[40] These, of course, were

the deluxe version of the day. Cheaper rolls could be bought in bookstores and

prices were quite low, because of the cheap labour provided by the slaves

copying the texts, which made the volumes possibly cheaper than their equivalent

in our days.[41] These cheaper books, however, had a tendency to be eaten by

insects, used by cooks to wrap meat or used as scrap paper by students to write

on the back of the papyrus.[42] This would change somewhat with the advent of

the codex, but even in that case, the book might be erased and the vellum or

parchment written over.

In the earlier days of the late republic, librarians were usually slaves. A

famous librarian in charge of private libraries was Tyrannion, who was brought

by Lucullus to Rome in 72 BC. He gained his freedom, then advised such men as

Cicero and Sulla on their collections and did some cataloguing for Cicero. We

also know that a citizen such as Varro did some collecting for Caesar. Sulla’s

library was supposed to have been catalogued by Andronicus of Rhodes. During the

principate, there was an official in charge of public libraries known as the

procurator bibliothecarium. Some famous holders of this office were Dyonisus of

Alexandria (around 100 CE), who was also Trajan’s secretary; C. Julius Vesinus,

appointed under Hadrian, and who later became director of the Alexandria Museum;

the famous writer Suetonius also held this position under Hadrian, and an

inscription tells us that a Q. Vetturius Callistratus held it in 250 CE or so.[43]

By the mid-2nd Century CE, this position had been split into several, because

there were just too much administrative duties pertaining to libraries.[44]

Subordinates of these officials were numerous: each library had its librarian

and underlings. The librarian was called bibliothecarius or magister. Some known

librarians were Hyginus Melissus and Pompeius Macer under Augustus; Tiberius

Julius Pappus under Tiberius, Caligula and Claudius; Scirtus under Claudius,

etc. Some of these officials were not only in charge of one library but also of

several, and sometimes, of all the libraries in the City.[45] Other workers

included the librarius, who did cataloguing and copying; the vilicus, who was a

“general attendant”[46] and the antiquarius, who was the resident scholar.

The top jobs seem to have been political plums (the top position was part of an

equestrian cursus that comprised, amongst others, military posts),[47] whereas

assistants did the actual work. Booksellers often helped with selection and

acquisitions, especially in private libraries.[48]And emperors in later

centuries seem to have not employed slaves for their private libraries: it is

noted that Julian appointed a Greek physician, Oribasius, to care for his own

private library.[49]

Cataloguing was usually done according to subject, within the two major

divisions of Greek and Latin. We don’t know exactly what the classifications

were, but it appears that the works of an author would be kept together under

his subject of expertise. Different philosophies were separated and so were the

religions. The catalogue was either a sort of shelf list or a bibliographical

catalogue.[50]

Some specific private libraries one should look at to get a sense of the

diversity of private libraries at the top levels of Roman society are the ones

described in detail in Lorne Bruce’s excellent paper “Palace and Villa

Libraries from Augustus to Hadrian”. These are the Villa of Papyri, The House

of Menander, the House of Augustus, the Domus Aurea, and the libraries in the

Villa Adriana, the Villa Jovis and the Domus Tiberiana.

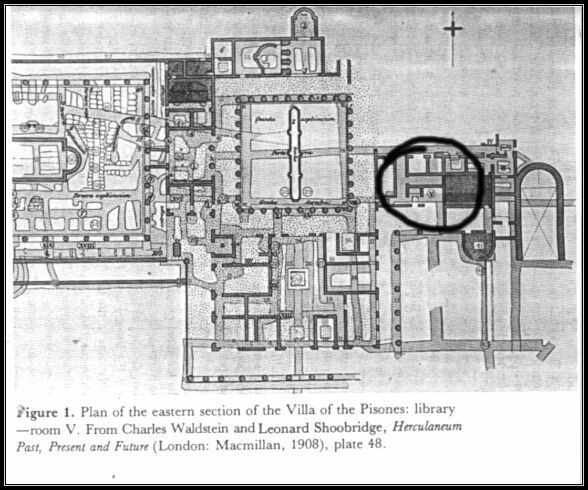

I would like to discuss one of these, the Villa of Papyri of Herculaneum,

further. This one is very much in the news these days, because of new

technologies helping to shed light on some of its secrets. It is the only Roman

library in which we have found actual volumes, over 1800 scrolls in this case,

mostly of Epicurean writings, and principally from the philosopher Philodemus.

It appears that this library belonged either to the philosopher himself, or most

likely, to the family of his patron, the wealthy father-in-law of Julius Caesar,

L. Calpurnius Piso. This was a small library, measuring 3.2 x 3.2 meters (room V

in figure 1). Its floor was decorated with mosaic. Its interior walls had burnt

wooden shelves up to 1.8 meters. An armarium with two-sided shelves containing

thousands of papyri rolls was in the centre of the small room. Small metal

plates that might have been shelf labels were discovered on the floor of the

library and nearby.[51] The room was so small it must have not been meant for

reading. This may have been the purpose of the smaller room beside the library

room. And reading may have been accomplished at several other places in the

villa as well, because papyri were found at various locations within the

villa.[52]

The library was first discovered in the 1750s, when diggers tunnelled through

over 65 feet of mud and lava from Vesuvius’s 79 CE eruption. All through the

18th to 21st centuries, the rolls have undergone various processes to try and

unroll them. Many of these attempts did not succeed, but many also did, which is

how we know that the majority of the works are Philodemus’s. A new

multi-spectral imaging technology is now being used to decipher these rolls, and

much writing that could not be read before can now be understood. This may lead

to lost works by Aristotle, Philodemus, Virgil, Epicurus, Archimedes and Sappho

being brought back to light. Another tantalizing possibility is that new rolls

may be discovered in a newfound basement of the villa.[53] One must remember

that many Roman libraries at Rome had the two collections, and that so far, we

had known only the one library in this villa with its almost entirely Greek

collection: a Latin-language library may still be lurking underground, waiting

to be discovered.[54]

What did we inherit from Roman private libraries? I doubt that any works came to

us from the public libraries of Rome, because these were a prime target for

burning and destruction, and there is no record of them surviving past the 6th

century. Many works were also preserved in the Eastern Empire, until its

destruction by the Turks in the 15th century, and some of these were passed on

to us. As we saw earlier, many Roman works were saved by libraries on the

outlying frontiers of the Western Empire, and passed down to us through the

monasteries of the Middle Ages and the rediscoveries of the Renaissance. It is

fortunate that there were so many private libraries in Rome and its Empire, with

so much content duplication, because otherwise, we would have lost even more

classics than we already have. And there is still the possibility that other

finds akin to those of the Villa of Papyri may surface, and help us regain a bit

more of the lost literature and knowledge of our Roman predecessors.

___________________

Bibliography

Primary sources:

Seneca

Ammianus Marcellinus

Petronius

Pliny the Younger

Pliny the Elder

Plutarch

Suetonius

Vitruvius

Horace

Polybius

Monographs and articles:

Boren, Henry C., Roman Society, (Lexington, 1992)

Boyd, Clarence Eugene, Public libraries and literary culture in ancient Rome,

(Chicago, 1915)

Bruce, Lorne D., “A Note on Christian Libraries during the “Great

Persecution”, 303-305 A.D.”, JLH 15 (2) Spring 1980, 127-137

Bruce, Lorne D., “A Reappraisal of Roman Libraries in the Scriptores Historiae

Auguste”, JLH 16 (4), Fall 1981, 551-573

Bruce, Lorne D., “Palace and Villa Libraries from Augustus to Hadrian”, JLH

21 (3), Summer 1986, 510-552

Bruce, Lorne D., “Roman Libraries: A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35 1985,

89-106

Bruce, Lorne D., “The Procurator Bibliothecarium at Rome”, JLH 18 (2),

Spring 1983, 143-162

Cameron, Averil, The Later Roman Empire, (London, 1993)

Cameron, Averil, The Mediterranean World in late Antiquity, (New York, 1996)

Canfora, Luciano, “Les bibliothèques anciennes et l’histoire des textes”,

in Baratin, Marc and Jacob, Christian, Le pouvoir des bibliothèques, (Albin

Michel, Paris, 1996)

Chisolm, Kitty and Ferguson, John, Rome – the Augustan Age, (Oxford, 1981)

Cizek, Eugen, Néron, l’empereur maudit, (Fayard, France, 1982)

Dix, T. Keith, ““Public Libraries” in Ancient Rome: Ideology and Reality”,

Libraries & Culture 29 (3), 1994, 282-296

Dix, T. Keith, “Pliny’s Library at Comum”, Libraries & Culture 31 (1),

Winter 1996, 282-296

Durant, Will, Le Christ et César, (Lausanne, 1963)

Gigante, Marcello, Philodemus in Italy, (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1990)

Hadas, Moses, Imperial Rome, (New York, 1965)

Harris, Michael H., History of libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen, N.J.,

1995)

Harris, William V., Ancient literacy, (Harvard, 1989)

Henrichs, Albert, “Graecia Capta: Roman Views of Greek Culture”, Harvard

Studies in Classical Philology 97, 1995, 252-254

Horsfall, Nicholas, “Empty Shelves on the Palatine”, Greece & Rome XL

(1), April 1993, 58-67

Houston, George W., “A Revisionary Note on Ammianus Marcellinus 14.6.18: When

did the Public Libraries of Ancient Rome close?”, Library Quarterly 58 (3),

258-264

Johnson, David Ronald, “The Library of Celsus, An Ephesian Phoenix”, Library

Bulletin, June 1980, 651-653

Kent, Allen et al., Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, vol. 26,

(New York, 1979)

Kenyon, Frederic G., Books and readers in Ancient Greece and Rome, (Oxford,

1951)

Kuttner, Ann, “Republican Rome looks at Pergamon”, Harvard Studies in

Classical Philology 97, 1995, 164-165

Lewis, Naphtali and Reinhold, Lewis, Roman Civilization, volume 1, (New York,

1990)

Murphy, Christopher, “Rome, Ancient” in Wiegand, Wayne A., and Davis, Donald

G. Jr., Encyclopedia of Library History, (New York, 1994)

Scullard, H.H., From the Gracchi to Nero, (New York, 1959)

Sider, Sandra, “Herculaneum’s Library in 79 A.D.: The Villa of the Papyri”,

Libraries and Culture 25 (4), Fall 1990, 534-542

Smith, William, The Wordsworth Classical Dictionary, (London, 1880)

Starr, Raymond J., “The Circulation of Literary Texts in the Roman World”,

CQ 37 (1) 1987, 213-223

Syme, Ronald, The Roman Revolution, (Oxford, 1939)

Takács, Sarolta, “Alexandria in Rome”, Harvard Studies in Classical

Philology 97, 1995, 270-272

Web sites:

http://www.roman-emperors.org/ : “De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online

Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors”

http://dsc.discovery.com/news/briefs/20010212/scrolls.html : Discovery News,

Lorenzi, Rossella, “New Tech Reads Ancient Roman Texts”

http://www.crystalinks.com/romeliterature.html : Crystal, Ellie, “Ancient

Roman Literature & Libraries”

http://www.humnet.ucla.edu/humnet/classics/Philodemus/Philhome.htm : The

Philodemus Project at UCLA

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy, (Harvard, 1989), p. 228

[2] Albert Henrichs, “Graecia Capta: Roman Views of Greek Culture”, Harvard

Studies in Classical Philology 97, (Harvard, 1995), p. 253; Plut., Aem. 28.11;

Polyb. 31.23.4

[3] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), pp. 56-57; Plut., Lucullus, XLII

[4] Clarence Eugene Boyd, Public libraries and literary culture in Ancient Rome,

(Chicago, 1915), p .53

[5] Suet., Div. Jul., XLIV

[6] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 57; Pliny the Elder, HN 7.30, 35.2

[7] Allen Kent et al., “Roman and Greek Libraries” in Encyclopedia of

Library and Information Science, Vol. 26 (New York, 1979), p. 21

[8] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), pp. 58; Suet., Dom. XX

[9] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 58

[10] Christopher Murphy, “Rome, Ancient” in Encyclopedia of Library History,

(New York, 1994), p. 556

[11] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), pp. 58-59

[12] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 61

[13] Christopher Murphy, “Rome, Ancient” in Encyclopedia of Library History,

(New York, 1994), p. 555

[14] T. Keith Dix, “Pliny’s Library at Comum”, Libraries & Culture,

Vol. 31, No. 1, Winter 1996 (Austin, 1996), p. 85

[15] This library included a crypt for his sarcophagus: David Ronald Johnson,

“The library of Celsus, an Ephesian Phoenix”, Library Bulletin, June 1980, p

.651

[16] T. Keith Dix, “Pliny’s Library at Comum”, Libraries & Culture,

Vol. 31, No. 1, Winter 1996 (Austin, 1996), pp. 85, 89-90

[17] Lorne Bruce, “Roman Libraries, A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35, (Copenhagen,

1985), p. 99

[18] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 63

[19] T. Keith Dix, “‘Public Libraries’ in Ancient Rome: Ideology and

Reality”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 29, 1994 No. 3, p. 287

[20] T. Keith Dix, “‘Public Libraries’ in Ancient Rome: Ideology and

Reality”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 29, 1994 No. 3, p. 285

[21] T. Keith Dix, “‘Public Libraries’ in Ancient Rome: Ideology and

Reality”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 29, 1994 No. 3, p. 285

[22] T. Keith Dix, “‘Public Libraries’ in Ancient Rome: Ideology and

Reality”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 29, 1994 No. 3, p. 282

[23] T. Keith Dix, “‘Public Libraries’ in Ancient Rome: Ideology and

Reality”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 29, 1994 No. 3, p. 283; Horace,

Epistle 1.3.15-20

[24] Raymond J. Starr, “Circulation of Literary Texts in the Roman World”,

CQ 37 (i) 1987, p. 216 ff.

[25] Nicholas Horsfall, “Empty Shelves on the Palatine”, Greece & Rome

XL, No. 1, (Oxford, April 1993), p. 61

[26] Suet., Div. Jul. LVI

[27] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 66

[28] Lorne D. Bruce, “A Note on Christian Libraries during the ‘Great

Persecution,’ 303-305 A.D.”, The Journal of Library History, Vol. 15, No. 2,

Spring 1980, pp. 127 ff.

[29] Clarence Eugene Boyd, Public libraries and literary culture in Ancient

Rome, (Chicago, 1915), p .66

[30] Frederick G. Kenyon, Books and Reading at Rome, 2nd Ed. (Oxford, 1951), pp.

82-83; Seneca, De Tranquilitate Animi, IX; Petronius, Cena Trimal. XLVIII

[31] George W. Houston, “A Revisionary Note on Ammianus Marcellinus 14.6.18:

When Did the Public Libraries of Ancient Rome Close?”, Library Quarterly vol.

58, No. 3 (Chicago, 1988), pp. 258-264

[32] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 67

[33] Sarolta A. Takács, “Alexandria in Rome”, Harvard Studies in Classical

Philology 97, (Harvard, 1995), p. 271

[34] Lorne Bruce, “Roman Libraries, A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35, (Copenhagen,

1985), p. 91

[35] Lorne Bruce, “Roman Libraries, A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35, (Copenhagen,

1985), p. 93

[36] Lorne Bruce, “Roman Libraries, A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35, (Copenhagen,

1985), p. 94

[37] Lorne Bruce, “Roman Libraries, A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35, (Copenhagen,

1985), p.103

[38] Vitruvius VI.4.I

[39] Lorne Bruce, “Roman Libraries, A Review Bibliography”, Libri 35, (Copenhagen,

1985), p. 95

[40] Frederick G. Kenyon, Books and Reading at Rome, 2nd Ed. (Oxford, 1951), p.

84

[41] Clarence Eugene Boyd, Public libraries and literary culture in Ancient

Rome, (Chicago, 1915), p .62

[42] Frederick G. Kenyon, Books and Reading at Rome, 2nd Ed. (Oxford, 1951), p.

84

[43] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 65

[44] Lorne Bruce, “The Procurator Bibliothecarium at Rome”, JLH 18 (2),

Spring 1983, p. 153

[45] Lorne Bruce, “The Procurator Bibliothecarium at Rome”, JLH 18 (2),

Spring 1983, pp. 149 ff.

[46] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 65

[47] Lorne Bruce, “The Procurator Bibliothecarium at Rome”, JLH 18 (2),

Spring 1983, pp. 144-145: The Equestrians were the second order of Rome, after

the Senators, and were usually merchants, bureaucrats, or administrators, both

civil and military.

[48] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), p. 65

[49] Lorne Bruce, “The Procurator Bibliothecarium at Rome”, JLH 18 (2),

Spring 1983, p. 158

[50] Michael H. Harris, History of Libraries in the Western World, (Metuchen,

1995), pp. 65-66

[51] Sandra Sider, “Herculaneum’s Library in 79 A.D.: The Villa of the

Papyri”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 25, No. 4, Fall 1990, pp. 537-538

[52] Lorne Bruce, “Palace and Villa Libraries from Augustus to Hadrian”, JLH

21 (3), Summer 1986, p. 512

[53] http://dsc.discovery.com/news/briefs/20010212/scrolls.html : Discovery

News, Lorenzi, Rossella, “New Tech Reads Ancient Roman Texts”, February 21,

2001

[54] [54] Sandra Sider, “Herculaneum’s Library in 79 A.D.: The Villa of the

Papyri”, Libraries & Culture, Vol. 25, No. 4, Fall 1990, pp. 539

Appendix 1 – Table of important events in Rome and

its libraries

|

Dates |

Rulers, politicians and military leaders |

Important political and military events |

Important writers (Christian writers in italics) |

Libraries, their owners, founders and officials (Important private libraries in italics) |

|

The Kings 753-509 BC |

7 kings (legendary) |

Conquest of Latium, Rome dominated by the Etruscans |

Rome bases its alphabet on the Greek alphabet |

|

|

The Republic 509-44 BC |

Scipio Africanus Scipio Aemilianus The Gracchi Marius Sulla Pompey Crassus Caesar |

Conquest of Italy, North Africa, Greece, etc. The Gauls sack Rome Plebeians allowed to hold office Punic Wars Mithridatic wars Spartacus revolt Conquest of Gaul, Civil war |

The Twelve Tables, Cato, Polybius, Lucretius,

Cicero, Caesar, Varro, Sallust, Diodorus Siculus |

The Villa of Papyri, apparently belonging to

L. Calpurnius Piso Caesonius, Julius Caesar’s father-in-law containing

works by Philodemus (d. 40/35 BC) and others Lucullus’ (d. 55 BC) Library |

|

±44

BC (end of the Republic) |

Julius Caesar, dictator for life, assassinated on

the Ides of March |

|

|

Varro asked to found a public library in Rome by

Caesar, does not have time to do it because his patron is assassinated on

the Ides of March 44 BC, finally accomplished by Asinius Pollio |

|

44 BC-14 CE |

Lepidus, Mark Antony, Octavian-Augustus |

Civil war, Battle of Actium, 31 BC, death of Mark

Antony and Cleopatra, Conquest of Egypt |

Livy, Ovid, Virgil, Horace, Dionysius of

Halicarnassus, Propertius, Vitruvius, Strabo |

House of Menander House of Augustus

Pompeius Macer, in charge of libraries at Rome |

|

14–37 |

Tiberius |

Crucifixion of Jesus, Fall of Sejanus |

Seneca the Elder, Velleius Paterculus, Philo,

Valerius Maximus |

Domus Tiberiana Villa Jovis |

|

37-41 |

Caligula |

|

|

|

|

41-54 |

Claudius |

Conquest of Britain |

Claudius |

|

|

54-68 |

Nero |

Fire in Rome (64 BC) |

Seneca the Younger, Petronius, Columella, Paul |

Domus Aurea |

|

68-69 |

The year of the four emperors |

Civil war |

|

|

|

69-79 |

Vespasian |

Jewish revolt crushed |

Pliny the Elder, Quintilian |

|

|

79-81 |

Titus |

Eruption of Vesuvius in 79 |

Flavius Josephus |

Burial of the Villa of Papyri and of the House

of Menander under Vesuvius’ ashes |

|

81-96 |

Domitian |

|

Frontinus, Martial |

Domitian restores public libraries burned under

Nero |

|

96-98 |

Nerva |

|

|

|

|

98-117 |

Trajan |

The Empire is at its maximal size, 1st

non-Italian emperor |

Dio Chrysostom, Plutarch, Tacitus, Pliny the

Younger |

Trajan razes the Domus Aurea Ulpian Library Pliny’s library at Comum |

|

117-138 |

Hadrian |

|

Juvenal, Suetonius, Florus |

Suetonius, Procurator

Bibliothecarium (or a

bibliothecis) Hadrian’s Villa Athens library |

|

138-161 |

Antoninus Pius |

|

Appian, Aulus Gellius, Justin Martyr |

|

|

161-180 |

Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus (161-166) |

Continuous fighting on the German border |

Marcus Aurelius, Fronto, Apuleius, Pausanias |

|

|

180-192 |

Commodus |

|

|

|

|

192-193 |

Pertinax, Didius Julianus (193) |

Civil war |

|

|

|

193-211 |

Septimius Severus |

|

Plotinus |

|

|

211-217 |

Caracalla, Geta (211) |

Caracalla makes all free inhabitants of the Empire

officially Roman citizens |

|

|

|

217-218 |

Macrinus |

|

|

|

|

218-222 |

Elagabalus |

Elagabalus tries to change the main god of Rome to

the “Sun-god” |

Tertullian, Origen |

|

|

222-235 |

Severus Alexander |

|

Cassius Dio, Athenaeus |

Pantheon Library |

|

235-284 |

Period of turmoil (the 26 or so “barracks

emperors”) |

50 years of anarchy in the provinces and at Rome |

Herodian, Cyprian, Minucius Felix |

|

|

284-305 |

Diocletian and the tetrarchy |

Last persecution of the Christians |

|

Burning of Christian Libraries |

|

306-337 |

Constantine I and family |

Edict of Milan: all religions allowed to flourish

without persecution, Council of Nicaea |

Lactantius, Eusebius,

Historia Augusta |

|

|

337-361 |

Constantius II |

|

|

|

|

361-392 |

Julian, Jovian, Valentinian I, Valens, Gratian, Valentinian II |

Julian tries to restore paganism, fails |

Eutropius, Julian, Libanius, Symmachus |

Antioch Library |

|

378-395 |

Theodosius I |

Christianity becomes the official religion of the

Empire |

Ammianus Marcellinus, Claudian, Jerome |

Ammianus tells us that Roman libraries are now like

“tombs” |

|

393-425 |

Honorius (393-423) and others (Western Empire) |

Split of the Empire in western and eastern parts

(395), Britain lost, Sack of Rome by Alaric and the Visigoths (410) |

Macrobius, Augustine, Orosius |

|

|

425-455 |

Valentinian III (Western Empire) |

|

|

|

|

455-476 |

Decay and end of the Western Roman Empire, Romulus

Augustulus, last emperor (475-476) |

“Fall of Rome” |

Zosimus |

The Ulpian Library is still extant in 480 CE, last

mention of a Roman public library in the Western Roman Empire |